Project to reconnect Native American tribes with historic hide painting, artistic tradition

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — The Native American tribes that once called Illinois home painted deer and bison hides with stories and symbols that were important to their culture. Some of the best examples of this artistic tradition – four painted hide robes made sometime between 1680 and 1750 – are now in the collection of the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris.

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign history professor Robert Morrissey is working with an interdisciplinary group of scholars, tribal cultural experts and community members on a project that will reconnect the tribes with their tradition of hide painting and with the ceremonial robes in the Quai Branly Museum.

The three-year project, “Reclaiming Stories: (Re)connecting Indigenous Painted Hides to Communities through Collaborative Conversations,” is a collaboration between the U. of I., the Myaamia Center at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, the Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma and the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma. It is funded by a Grand Research Challenge grant from Humanities Without Walls, a research consortium based at the U. of I.’s Humanities Research Institute and supported by the Mellon Foundation. The purpose of the grant is to support research partnerships with experts outside of academic institutions.

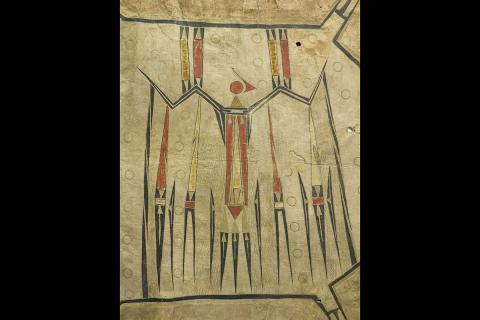

The four hide paintings are associated with the Illinois and Miami tribes and are part of a large collection of objects from the colonial period at the Paris museum, including painted hide bags and shirts. They include one of the most famous existing hide paintings from the 18th century – a robe featuring an iconic image of a thunderbird painted in shades of rust, gold and black.

“It is very well-known and one of the most celebrated pieces of Indigenous art from this period,” Morrissey said. “Plains Indians used hide paintings as a documentary medium, for depictions of battles and events. These are different. Their designs are abstract. Even if they don’t tell stories, they are very important documents of their history and culture.”

Members of the Miami and Peoria tribes have been reconnecting with many parts of their culture – including their language, ecological knowledge, artistic and cultural traditions – that had been dormant for many generations.

“That spirit of reawakening is very clearly a part of this project,” Morrissey said. “A big part of this project is to help the Miami and Peoria communities continue to revitalize their cultures in a hands-on way. It’s more than an academic study of the past.”

The project held its first major event in early August – a learning lab featuring a workshop on hide painting, held in Miami, Okla., the governmental seat of the Miami and Peoria tribes. Tribal members studied the history of the artistic tradition. Then Indigenous artists Michael Galban and Jaime Jacobs led them in mixing paints by grinding rocks with a high iron content to create a deep rust color.

They used wood styluses to apply the paint to deer hides and also to scratch designs into the hides, copying motifs from paintings made hundreds of years ago. Then they sewed the hide panels together into bags that traditionally would have been used for carrying tobacco or other utilitarian purposes but also were decorative.

The project team also presented its work to the tribal communities.

In addition to revitalizing aspects of Indigenous culture, the project aims to add the knowledge of the tribes to create a deeper understanding of the hide paintings and their significance, Morrissey said. The Quai Branly Museum has a new curatorial program to collaborate with tribes and center Indigenous knowledge in its interpretive programs.

“Museums always have been the ones to tell the world about these objects in an official way,” Morrissey said. “This project aims to decolonize the objects and reconnect them with the descendants of the people who made the art and whose ideas are embodied in the art.”

Morrissey said the project team plans to hold another learning lab to continue to teach the tribes’ crafts and to organize a seminar with an anthropologist and art historian who will talk about the cultural traditions.

Project team members hope to enable a group of tribal leaders to travel to Paris on a research trip to see the hide paintings and to study the art practices, diplomacy and ceremony, and the history of Indigenous people in Paris, Morrissey said. Ultimately, the group plans to create a major exhibition on what they have learned about the hide paintings that will premiere at the Miami University Art Museum and travel to Miami, Okla., and possibly other locations.

Editor’s note: To contact Robert Morrissey, email rmorriss@illinois.edu.

By Jodi Heckel, Arts and Humanities Editor, Illinois News Bureau. This story was originally published on November 16, 2022.