Reclaiming Stories through Indigenous Practices

Community-Based Collaboration Supports Cultural Revitalization Process

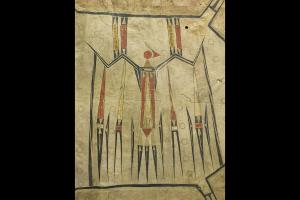

featuring an iconic image of a

thunderbird, now in the collection

of the Musée du Quai

Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris

What does public humanities research look like when community need and knowledge making are brought to the fore? Enter the Reclaiming Stories project, a Grand Research Challenge-funded initiative that is helmed by an interdisciplinary team of researchers from the Miami and Peoria tribal nations, as well as academics from institutions across the country. Together, the Reclaiming Stories team aims to revitalize the Indigenous cultural practices of hide painting in partnership with citizens of the Myaamia and Peewaalia community.

We spoke with team members George Ironstrack (Miami), Liz Ellis (Peoria), Bob Morrissey, and Cam Shriver, who outlined the complexity and the importance of engaging in this cross-institutional, multi-national endeavor.

What can cultural revitalization look like?

Bob Morrissey: It’s a really exciting project in part because it's connected to an ongoing story of revitalization and cultural reawakening in these two Indigenous nations, Myaamia and Peewaalia, or Miami and Peoria; that process has been ongoing for a couple of generations.

George Ironstrack: For the Myaamia community, we’ve experienced a lot of loss, since really the end of the 1800s, with the allotment of our last reservation in Oklahoma and the dispersal of people that came with the early 20th century. We had a lot of cultural loss, a lot of political loss. And we're seeking to rebuild and recover from that.

"We've very much explicitly adopted a tone of recognizing we're not trying to become our ancestors. We're trying to learn about what our ancestors did [...] and take the best of that to make us healthy and whole today." — George Ironstrack

Liz Ellis: Peoria, my community, like Miami, endured a really rough set of circumstances in Oklahoma. The nation was removed from Illinois, and [...] most of our community was sent to boarding schools and Indian day schools. By the mid 20th century, there were not a lot of language speakers.

Basically, there was a huge amount of cultural theft and destruction around the early 20th century. The tribe was technically ended by the federal government [in the 1950s], and re-recognized in the 1970s, thanks in large part to the efforts of my grandfather and a couple of others of his generation. They organized to bring the community into a political space where they were able to apply for re-recognition.

Cam Shriver: With the Miami and Peoria culture, the losses were significant. There was no land— zero. There were no speakers— zero. There were powwows, but there was no ceremony. Culture can only be carried by people, so where the people are coming from is from a place of pretty profound loss. The good thing is now we're on the other side of that. Those sleeping aspects of culture have been reawakened through research.

"Our project is a small chapter now of what's a much larger story, a much larger trajectory of a kind of cultural revitalization among these communities."

— Bob Morrissey

How did the collaboration emerge?

Bob Morrissey: We started our conversation [...] back three years ago or so informally over Zoom. I knew many of the folks in this group just from academic travels, conferences and the like, but my own mode of scholarship was single-author—behind the computer in the library, not engaged.

Liz Ellis: Within the community, folks joke, “You didn't come up with anything by yourself.” Every idea that you've had is because of a series of conversations and because of the milieu that you're raised in, that you exist in.

There's a little bit of a disjuncture, sometimes between those of us who pursue careers in institutions and in the academy, and the expectations for giving back within communities and the way that knowledge is produced […] the model for the Humanities Without Walls initiative is a beautiful way to support this kind of academic work, which is sometimes harder to recognize or to secure funds for.

Cam Shriver: How do you actually revitalize something? It takes a lot of money and time [for] people to be teachers. The grant has allowed us to continue to have those conversations and actually meet in person.

George Ironstrack: Our time is our most valuable thing in community revitalization. We don't dedicate time to something like this unless there's a need and an interest in the community writ large. In our community, there's a driving interest in the arts and in the practice of arts, as well as the revitalization of old arts that aren’t currently being practiced. Our motivating factor is community need and community interest.

What does this collaboration look like in day-to-day practice?

Bob Morrissey: What is definitely centered in this project is a sort of multi-vocal kind of approach. Our project very intentionally, both intellectually and institutionally, centers the communities and their goals and their priorities and and their knowledge.

George Ironstrack: There's a recognition that we need to have representation from the different communities involved, so the Miami wouldn't pursue this without the Peoria. There's a sense of [...] not wanting to step forward without being hand in hand with our relatives. I can just say that this team would probably be in place without the grant, but that the grant gives us an ability to pursue a level of work that we couldn't pursue without that support.

"We’re working in a way that is rigorous, both by the standards of the academy, but also that is rigorous in terms of its approval and engagement with community experts and cultural leaders. We're not kind of bypassing or privileging one set of knowledge over another." — Liz Ellis

Liz Ellis: It's been wonderful to have grad students in this space as well, because often in the academy, we train grad students to think of hierarchies of knowledge and approval in very specific kinds of ways. This has given us an opportunity to look at diffuse sets of knowledge and points of authority throughout the project.

What does it mean to work specifically with the tribal nations?

George Ironstrack: I think what the non-tribal participants had to develop an understanding of is that tribal governments, and those who work on behalf of tribal governments, have a lot of responsibilities that most Americans are completely unaware of. Frankly, this work is a very small part. People realize this is important work, but we have to keep it in perspective.

Liz Ellis: We are sort of one drop in a bucket of ultra urgent issues, vital things that the tribe has to invest resources in. [We] keep stuff moving and work at a pace that both accommodates the needs of tribal governments, and the interests of the project. It is really a challenge and something that we've been trying to manage with this grant. The longer timeline of the Humanities Without Walls grant has been really important there.

In what ways does gender play a role in facilitating this project?

Bob Morrissey: Running underneath the surface [of this project] is another dimension of reclaiming. It is an interesting kind of reclaiming and centering of knowledge-making around the authority of women who are in leadership roles at almost every level of the institutions that are involved here.

Liz Ellis: There's a real commitment among— I think this is true among Native men as well, but among Indigenous women to hold on to and be the bearers of culture, language. A lot of us raised within smaller communities, or people who are very aware of their nation's histories, feel this real obligation to continue to support and fight for the nations. People worked so hard to make sure that the Peoria nation and the Miami nation weren't gone in the 19th century.

George Ironstrack: We don't want to just obliterate [traditional] understandings [of gender]. We're not going to teach in our community that men can't paint hide robes. In fact, we're going to encourage men to learn to paint. But we do want to make sure that we're thinking through: Is there space for us to revitalize some of these gendered understandings and responsibilities? Because that will give us a certain kind of strength that our ancestors had.

What will that look like? I don't pretend to know. But we're certainly going to talk about it and consider it, as we revitalize this art form and the practices that are inherent to making it possible.

What does the academic impact of the Reclaiming Stories Project look like?

George Ironstrack: I’ve been a part of more classic academic grants with the final product as a white paper. And it goes on a shelf, and only 10 people ever read it. Which is not to say that it’s not valuable, but that's not what our community is asking for. The product has to be multi-faceted. In this specific case, the goal is connection to place, which is not something that's typical.

Cam Shriver: This [project has] a much more human processing method, which is talking things out deliberately and slowly for a long period of time. In the process of rediscovering these robes, you have to give them some time to breathe. You [have to] think about what connections they make through research and storytelling.

The audience isn't like an academic [one] who wants to learn about deer, but rather the people who will tell stories about the cinkweensaki (young thunder beings) who are represented on one of the robes. They'll have a deeper understanding of that character when they tell stories.

"The audience might be a future generation of story listeners."— Cam Shriver

What does the cultural impact of Reclaiming Stories look like?

George Ironstrack: The end product of ‘reclaiming stories,’ in terms of the process, it should engender is that the paints come from the land. The protein binders come from the land, from animals, or or plant sources, and then the hides come from the land. Hunted by our people and tanned by our people, and the act of producing new painted hide robes, Minohsaya, in the 21st century will be a community endeavor, rather than the product of an individual artist.

Liz Ellis: The questions are not just coming from those of us who are sitting in academic institutions, so part of the project has become that the community, the communities in Oklahoma, Miami and Peoria, want to know how to reproduce some of this stuff so that we can do hide painting workshops with our youth.

"A lot of native kids grew up with not a lot of good representations of themselves and not a lot of opportunities to participate in activities where they feel proud, they feel connected to their ancestry, they feel connected to their culture.[We want to make] space for those older practices in very modern settings." — Liz Ellis

It is important for building children's self esteem and for creating a next generation of Native kids who are not going to grow up feeling embarrassed that they're less than or that they don't know the old stories. These are really important parts of a history that, for generations, the federal government has worked very hard to disconnect us from.

Being able to paint on hide robes, and say, maybe using a plastic little tool to do the imprinting, or you're drinking a Juicy Juice while you do this. There's not a contradiction here, you can do both. This is authentic; this is important. This is what it means to be Peoria or Miami.

Photo credit for all images: Doug Peconge